Middle Palisade

When I think of Middle Palisade, I think first of the quiet beauty of the approach—the long hike to Finger Lake on day one, where the mountain slowly reveals itself. Day two is an entirely different story: crossing glacier-hard snow, a light scramble that quickly turns serious, and committing climbing where we wandered off route and had to dig deep to keep moving upward. The summit demanded patience and determination, and the descent unfolded beneath a rising moon. Middle Palisade is not an easy climb—but that’s exactly what makes it unforgettable.

Southfork Big Pine Creek Trailhead

🏞️ Highlights

Finger Lake: A stunning alpine lake at ~10,789 ft, framed by jagged peaks.

Brainerd Lake: Another popular destination along the trail.

Norman Clyde Glacier: Visible from higher sections, adding dramatic scenery.

Palisades Glacier: The largest glacier in the Sierra Nevada, looming above the trail.

Equipment

Helmet

Hiking poles

Overnight permit

Tent

Food and cooking utensils

Water filter

Mosquito repellent

No need for safety equipment (rope)

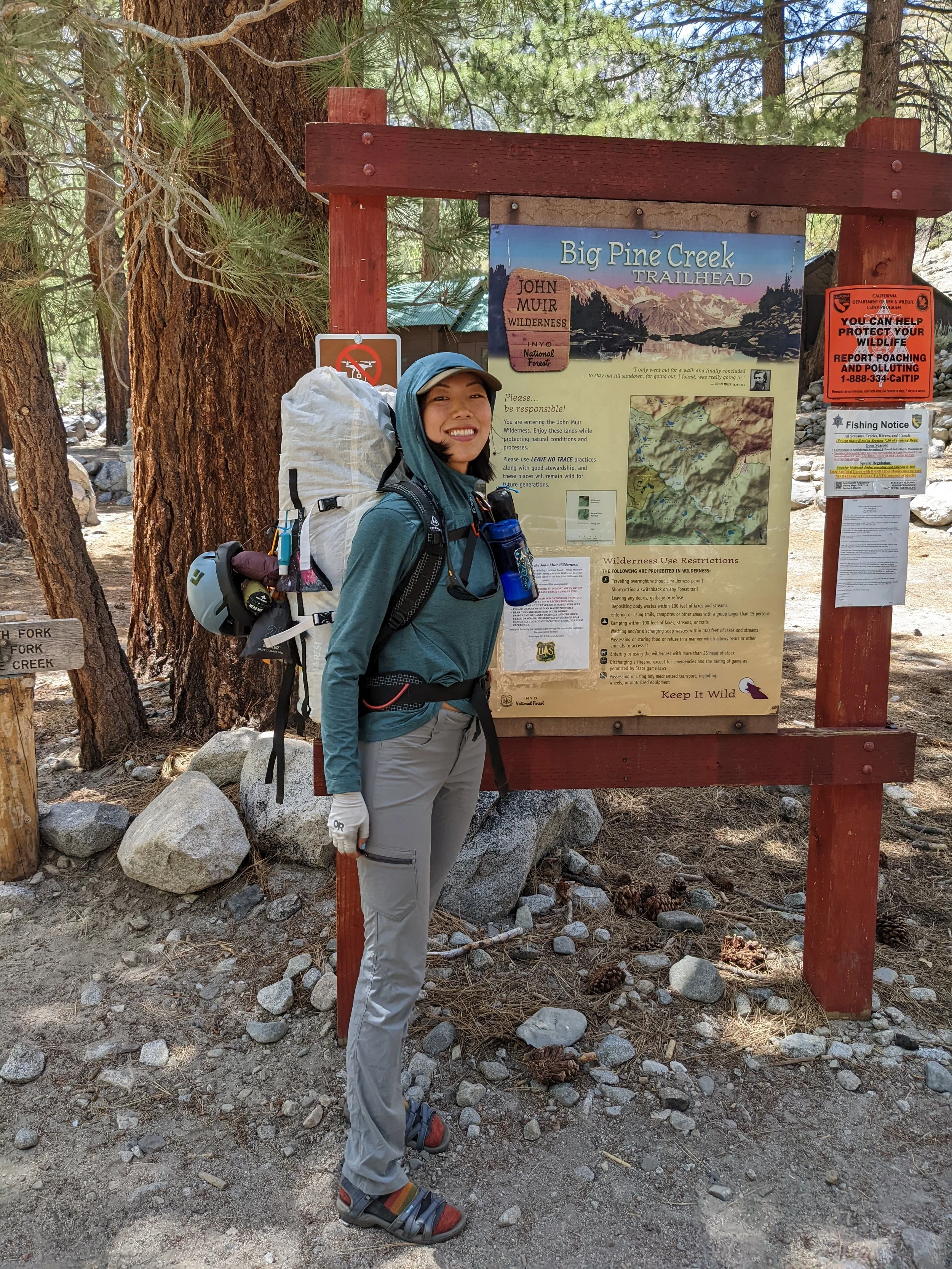

The trail began at the South Fork Big Pine Creek trailhead, where in July it was so hot at the trailhead and I couldn’t wait to get to higher elevation. Each step carried us deeper into the Sierra, the sound of rushing meltwater streams and the smell of pine needles underfoot setting the rhythm of the day. The climb was steady, and though the mosquitoes were relentless in July, we laughed them off, swatting and moving quickly, determined not to let them steal the joy of the scenery around us.

As the miles passed, the granite walls grew taller and the valleys opened wide, revealing glimpses of Brainerd Lake shimmering in the distance. By the time we reached it, the light had softened into late afternoon gold, and the lake mirrored the jagged peaks above. It was tempting to pitch camp right at the water’s edge, but the swarms of mosquitoes reminded us to keep our distance. We found a spot tucked back just far enough to enjoy the view without becoming their feast.

Setting up camp was its own ritual: the quiet clink of tent poles, the rustle of sleeping bags, the careful stashing of food. We packed our bags for the next day before the light faded, knowing that an early start would be easier if everything was ready. I had brought an extra trailrunner vest instead of my usual backpack, worried that scrambling over granite would leave my pack torn and scratched. It turned out to be the right choice — light, snug, and perfect for the rocky sections where balance mattered more than bulk. As the evening settled in, we sat near the lake, not too close, watching the last light fade from the peaks. The mosquitoes buzzed, but the wilderness was bigger than them, and the memory of that day was one of resilience, laughter, and the quiet beauty of the Sierra Nevada.The hum of mosquitoes was still there, but it became background noise to the crackle of conversation and the satisfaction of being out in the wild.

The next morning began in that quiet, alpine way — the air still cool, the light just starting to touch the tops of the peaks. We stirred at 6 a.m., pulling on layers and fumbling with breakfast while wearing mosquito nets over our heads, a comical but necessary shield against the relentless swarms. By 7 a.m., packs were on, poles in hand, and we were moving again, the trail pulling us upward.

The climb toward Brainerd Lake was steep but manageable, each switchback opening up new views of granite walls and the shimmering water below. Once past the lake, the terrain shifted into a playground of boulders, where every step was a hop or scramble, testing balance and patience. Beyond that, the glacier awaited — a vast sheet of snow and ice, glinting under the morning sun.

Crossing it was both exhilarating and humbling. The sun had already begun to soften the surface, leaving behind sun cups — those strange, uneven depressions in the snow that made each step a careful calculation. Walking across them felt like balancing on a frozen honeycomb, the risk of slipping always present. My pole became more than just gear; it was a lifeline, steadying me as I picked my way across the melting surface.

The heat of the day pressed down, but the brilliance of the glacier and the surrounding peaks made the effort worthwhile. It was the kind of moment where discomfort faded into awe, where the Sierra reminded us that beauty often comes with challenge.

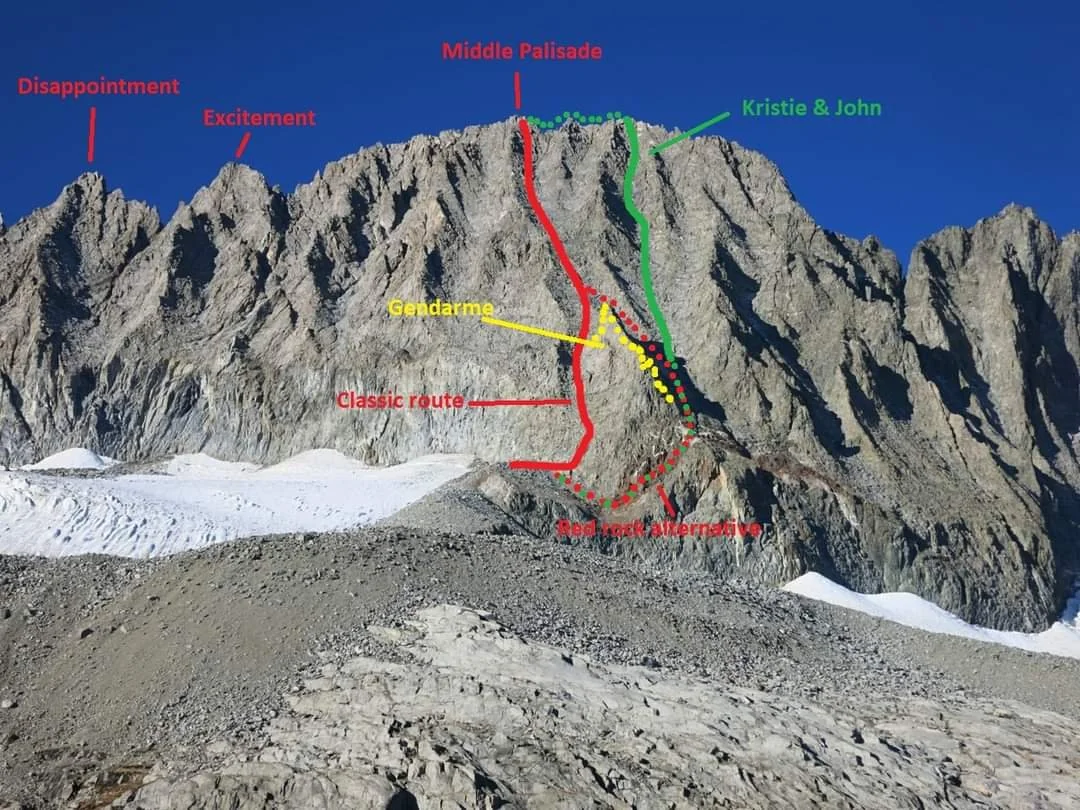

Our approach to Middle Palisade began as planned, weaving our way up the red rocks that guard the mountain’s flanks. The rock was solid enough, the holds reassuring, and for a while it felt like we were exactly where we needed to be. Somewhere along the way, I found a pink ATC in good shape! But somewhere near the so‑called Gendarme feature, we veered right instead of left — straying from the standard route. At first, it seemed fine; the terrain was steep but manageable, and the sense of progress kept us moving. Yet as we scrambled higher, pulling ourselves onto the highest point of the ridge we were on, the truth revealed itself: we weren’t on Middle Palisade at all, but north of it.

That realization carried a sting. The summit we sought was still out of reach, and the only way forward was down. We began the careful process of downclimbing, retracing our steps across exposed rock, every move demanding focus and composure. From there, we traversed toward the true summit, the mountain forcing us to earn every inch. The climb grew spicier, the holds thinner, the exposure greater.

The Summit

Pulling myself up after a tricky move, I finally popped onto the summit. In that instant, a flood of emotions overwhelmed me. For the first time in my life, I cried upon reaching a peak. Half of those tears came from sheer relief — the gratitude of being alive, of knowing there was hope for the descent, of realizing that the mountain had let me pass. The other half was pure satisfaction, pride in what had been achieved. The arduous two‑mile approach of boulder hopping and glacier crossing, followed by 2,000 feet of climbing, had pushed my technical ability and mental focus to their limits. And yet, here I was, standing on top. The ceiling of what once felt impossible had been shattered.

We were tired, and happy, and definitely emotional. We were scared that we coulnd’t come down the same way we went up, there were some climbing that I didn’t think I could downclimb on. When we reached the summit, we knew that we could come down the normal route. John had run out of water and luckily there was a gallon of water sitting in a gallon bottle at the summit! How crazy is that.

We summited around 3:30 pm, well into the afternoon, with sunset not until 8:00 pm. I was so grateful we’d brought our headlamps. We descended via the normal route, and I was relieved to be on familiar ground—most accidents happen on the way down, so we moved deliberately, carefully watching each step and avoiding loose rock.

By 6:30 pm, we were back on the glacier. The changing weather had hardened the snow, making it easier to walk. As we moved across it, Middle Palisade towered above us on the left—massive, quiet, and humbling.

We made it back to camp under a full moon. I was tired. But I knew deep in my heart that I had grown a little, and I will never climb Middle Palisade ever again.

Under the Watch of Middle Palisade

Adventures like these strip you down. The mountain doesn’t care about ego or bravado; it teaches humility, grace, humor, patience, and character in ways that no classroom ever could. Each challenge is a lesson in syncing with nature rather than fighting against it. By the end, I realized it was never me versus the mountain. It was me learning to move with the mountain, to quiet the whispering fears, and to find strength in the rhythm of rock, snow, and sky.